Beyond the bottleneck: Addressing Spain’s medical specialist shortage through strategic MIR* expansion and quality training

MIR*: Medical Intern Resident program

In Spain, the issue of whether there is a shortage of physicians is complex and multifaceted. While Spain boasts one of the highest numbers of physicians per capita in Europe, with 407 doctors per 100,000 inhabitants, the problem lies not in the overall number of physicians but in the distribution and specialization of these medical professionals. The country faces a significant challenge in certain specialties and geographic areas, particularly in small towns or rural regions, where filling positions remains difficult unless these roles are made more attractive through substantial professional and economic incentives.

A critical point of concern is the projected deficit of around 9,000 doctors by 2027, primarily due to shortages in Family and Community Medicine (MFyC) and other specialties. This deficit represents a turning point, signaling the need for immediate and long-term strategic planning to prevent exacerbating the situation. Short-term solutions could include increasing the number of Medical Intern Resident (MIR) positions in specific specialties, promoting immigration of trained doctors from other countries, and considering more flexible retirement policies within the National Health System (SNS).

Moreover, the aging workforce exacerbates the shortage, with a significant portion of European doctors being 55 years or older. This demographic trend is described as a «time bomb» by the World Health Organization, indicating an impending wave of retirements that could further strain the system. The situation is particularly acute in primary care, where there has been a notable reluctance among new doctors to fill vacancies in family medicine and pediatrics, leading to hundreds of MIR positions remaining unfilled in recent years.

Where is the imbalance between supply and demand of physicians?

he problem between the supply and demand of physicians in Spain is multifaceted, involving issues related to the distribution of medical specialists, the aging medical workforce, and the attractiveness of certain positions, particularly in rural areas or less popular specialties.

1. Specialization and Distribution: While Spain does not generally suffer from a lack of physicians, there is a notable deficit in certain specialties. The most significant shortages are observed in primary care, with lesser but still significant deficits in anesthesiology and psychiatry. Projections indicate a peak deficit of around 9,000 specialists by 2027, with specialties like Family and Community Medicine (MFyC), Occupational Medicine, Immunology, Psychiatry, Clinical Analysis and Biochemistry, and Microbiology expected to experience deficits greater than 10%.

2. Aging Workforce: The aging of the medical workforce is another critical issue. MFyC, for example, has one of the oldest age profiles among medical specialties, with a significant portion of professionals over 60 years old. This aging workforce is compounded by a trend of family doctors opting to work in the private sector or in emergency medicine, further exacerbating the shortage in primary care.

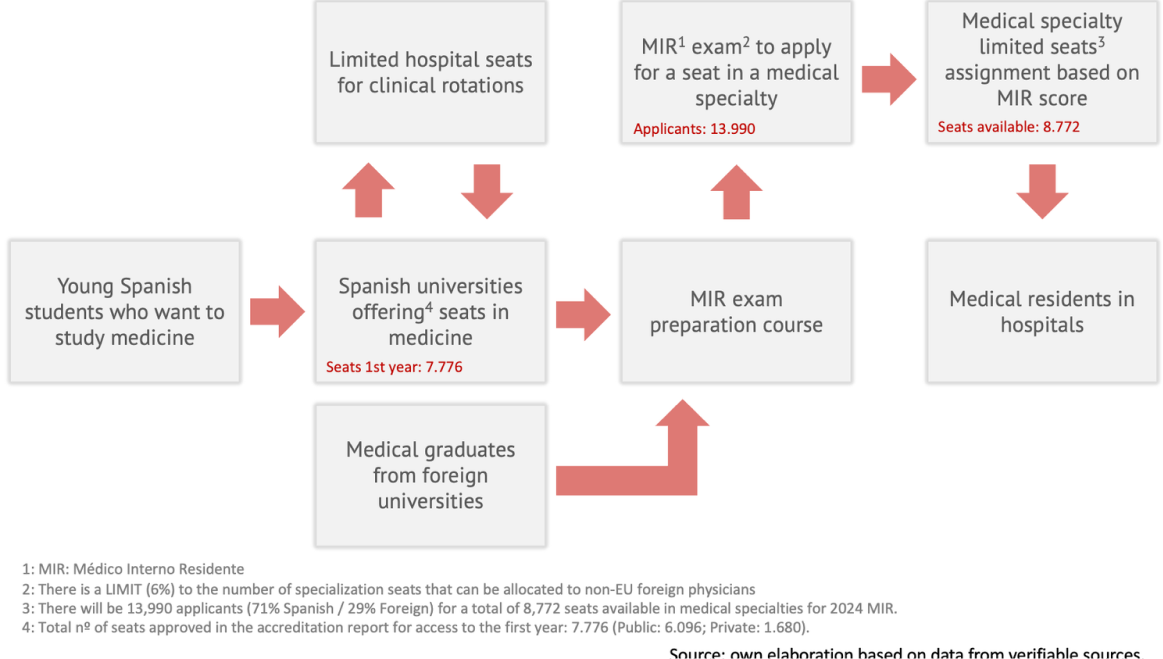

3. Training and Quality of Education: The bottleneck at the Medical Intern Resident (MIR) stage, which is the entry point into the healthcare system for specialists, is a significant obstacle. Spain produces a large number of medical graduates, but not all can enter the system due to limited MIR positions. Expanding MIR positions annually does not immediately solve the problem due to the time required for specialist training. There’s also a concern that increasing the number of training positions without ensuring the quality of training could compromise the quality of healthcare.

4. Attraction to Positions: The heterogeneity in the demand/need for physicians across specialties and the territorial distribution responds to the characteristics of the positions open for hiring. Some positions, particularly in less attractive locations or specialties, lack appeal and must be compensated with incentives to attract physicians.

Medical Intern Resident (MIR) stageclusion

The bottleneck at the Medical Intern Resident (MIR) stage represents a critical juncture in Spain’s healthcare system, significantly impacting the supply and demand of medical specialists. This limitation directly impacts the supply of medical specialists across various fields. For instance, the data shows a projected deficit in several specialties, indicating a mismatch between the supply of specialists and the demand within the healthcare system. Specifically, specialties such as Anesthesiology, Clinical Analysis, and Pathology are expected to experience significant deficits, with Anesthesiology having a 22.2% deficit, Clinical Analysis showing a 20.4% deficit, and Pathology facing a 76.4% deficit. This stage is crucial as it provides the necessary specialized training for medical graduates to become certified practitioners in their chosen fields. Despite Spain’s high production of medical graduates, the limited number of MIR positions (8.772 seats in 2024 MIR) means not all graduates (13.990 in 2024) can progress to become specialists, creating a significant obstacle in addressing the healthcare system’s needs.

Expanding MIR positions annually has been proposed as a solution to this bottleneck. However, this approach does not offer an immediate resolution due to the inherent time required for specialist training, which spans several years. Therefore, any increase in MIR positions today would only start to alleviate the specialist shortage several years down the line. This delay in the effects of policy changes underscores the complexity of planning for healthcare workforce needs and the importance of long-term strategic planning.

Moreover, there is a valid concern that merely increasing the number of training positions (+2.5% from 2022 to 2023) without parallel efforts to ensure the quality of training could lead to a dilution of healthcare quality. High-quality training is essential for producing specialists capable of delivering excellent patient care. Expanding training capacity without adequate resources, faculty, and infrastructure could compromise the training quality. This could, in turn, affect the overall quality of healthcare services, as the effectiveness of healthcare delivery heavily relies on the competence and expertise of its practitioners.

We can say while increasing MIR positions is a necessary step towards addressing the shortage of medical specialists in Spain, it is not a panacea. It must be accompanied by measures to ensure the quality of specialist training and a strategic approach to healthcare workforce planning that considers the time-lagged nature of training and its impact on healthcare delivery.

Doctors for Tomorrow: How Government Action Can Shape a Sustainable Medical Workforce in Spain

The government or Ministry of Health must play a leading role in addressing the bottleneck in the Medical Intern Resident (MIR) system through several key actions. Here few proposals for policy review:

Increasing MIR Positions: By annually expanding the number of MIR positions targeting specific specialities, the government can directly address the bottleneck. However, it’s important to note that the effects of such measures are not immediate due to the duration of medical specialty training. Any increase in MIR positions today will only start to alleviate the bottleneck after several years, highlighting the need for long-term planning.

Quality Assurance in Training: While increasing the number of training positions, the government must ensure that the expansion does not compromise the quality of training. High-quality specialist training is crucial for maintaining the standard of healthcare services. The Ministry of Health should implement and enforce strict quality control measures for training programs to ensure that the increase in quantity does not lead to a decrease in the quality of medical specialists.

Incentive Plans for Understaffed Specialties: To address the uneven distribution of medical specialists and the lack of interest in certain specialties, the government can develop incentive plans. These plans could include financial incentives, career development opportunities, and improved working conditions, particularly for primary care and specialties that are less popular among MIR candidates but are critical for the healthcare system.

Facilitating the Integration of Foreign-Trained Doctors: The situation of foreign students, particularly those coming to Spain to pursue medical careers, is influenced by the country’s economic cycles and the public healthcare spending trends. During the early 2000s up to 2008, there was an increase in the number of foreign doctors coming to Spain, many of whom were aiming to join the Medical Intern Resident (MIR) program. The peak year was 2008, with 7,709 foreign-trained doctors arriving in Spain. However, the economic crisis led to a significant reduction in these numbers, dropping to only 1,383 foreign medical professionals immigrating to Spain by 2015. This decline in immigration, especially from Latin American countries, reflects more on a decrease in demand (pull factors) rather than a push from their home countries. The Spanish healthcare system’s capacity to attract foreign medical professionals is closely tied to its economic health and the availability of positions within the MIR system.

By streamlining the recognition and integration process for foreign-trained doctors, the government can mitigate the shortage of medical professionals in certain areas and specialties. This could involve simplifying the homologation of foreign medical degrees and offering language and integration courses to ease their transition into the Spanish healthcare system.

Long-Term Workforce Planning: The government should engage in long-term healthcare workforce planning, taking into account demographic changes, disease prevalence, and healthcare delivery models. This involves not only adjusting the number of MIR positions but also forecasting the specialties that will be in high demand in the future and planning accordingly.

Expanding MIR positions annually has been proposed as a solution to this bottleneck. However, this approach does not offer an immediate resolution due to the inherent time required for specialist training, which spans several years. Therefore, any increase in MIR positions today would only start to alleviate the specialist shortage several years down the line. This delay in the effects of policy changes underscores the complexity of planning for healthcare workforce needs and the importance of long-term strategic planning.

Moreover, there is a valid concern that merely increasing the number of training positions (+2.5% from 2022 to 2023) without parallel efforts to ensure the quality of training could lead to a dilution of healthcare quality. High-quality training is essential for producing specialists capable of delivering excellent patient care. Expanding training capacity without adequate resources, faculty, and infrastructure could compromise the training quality. This could, in turn, affect the overall quality of healthcare services, as the effectiveness of healthcare delivery heavily relies on the competence and expertise of its practitioners.

We can say while increasing MIR positions is a necessary step towards addressing the shortage of medical specialists in Spain, it is not a panacea. It must be accompanied by measures to ensure the quality of specialist training and a strategic approach to healthcare workforce planning that considers the time-lagged nature of training and its impact on healthcare delivery.

Universities: Unclogging the Bottleneck in Medical Training with Strategic Reforms

Universities can play a pivotal role in addressing the bottleneck at the Medical Intern Resident (MIR) stage by implementing several strategic measures:

Enhancing Medical Curriculum: Universities can enhance their medical curriculum to better prepare students for the realities of the healthcare system, including offering more practical experiences and exposure to a variety of medical specialties. This could help students make more informed decisions about their specialty preferences, potentially easing the demand for the most oversubscribed specialties.

Collaboration with Healthcare Institutions: Universities can foster closer collaborations with healthcare institutions to create more training opportunities for medical students. This could include internships, shadowing programs, and research projects that provide students with real-world experience and networking opportunities within the healthcare system.

Career Guidance and Counseling: Universities can offer career guidance and counseling services to help students navigate the MIR selection process and explore alternative career paths within healthcare that may not require a MIR position. This could help distribute interest across a broader range of specialties and reduce the pressure on the most sought-after MIR positions.

Advocacy and Policy Engagement: Universities can play an advocacy role by engaging with policymakers to highlight the need for an increased number of MIR positions and improved distribution across specialties. By providing data and insights on the future healthcare workforce needs, universities can help shape policies that address the MIR bottleneck more effectively.

These efforts can help align the supply of medical graduates with the demand for MIR positions, ultimately contributing to a more balanced and efficient healthcare workforce.

To understand where the bottleneck occurs, the following diagram is presented:

References

Gamarra, M. (2023). Así queda el ranking de las universidades españolas con mejores notas en el MIR 2023. ConSalud.es

Castillo, M. (2024). MIR 2024: Qué esperar una vez hecho el examen de médicos residentes. Expansión.

Rivera, M. (2024). El MIR gana aspirantes en 2024: se presentarán 1.315 médicos más que en 2023. El Español.

Sánchez, F. (2022). «Es una bomba de relojería»: las autoridades alertan del riesgo de quedarnos sin médicos. El Confidencial. Alimente.

Sánchez, F. (2024). Cada vez hay más facultades de Medicina y más plazas MIR, pero siguen faltando médicos: ¿qué pasa en el sistema? El Confidencial. Alimente.

Europa Press (2023). Tomás Cobo: «En España no faltan médicos y la ratio por población es de las más altas de Europa». El Confidencial. Alimente.

Sánchez, F. (2023). 700 nuevas plazas en la universidad para paliar la falta de médicos: ¿va a servir para algo? El Confidencial. Alimente.

Barber, P. & López-Valcárcel, B. (2022). Informe Oferta-Necesidad de Especialistas Médicos 2021-2035. EcoSalud. Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.